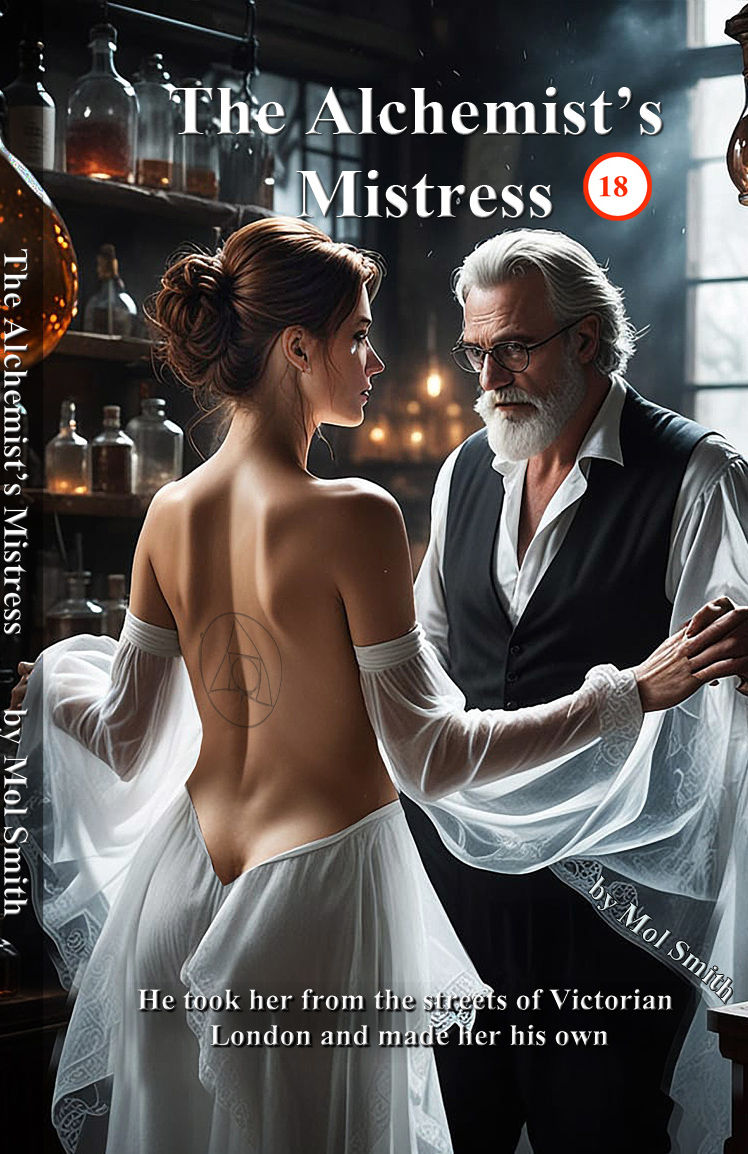

THE ALCHEMIST'S MISTRESS (close window to return)

|

A dark, foreboding, gothic take that's steeped in a claustrophobic, brooding style which haunts every page as a young woman is rescued from the streets to find herself the slave of an evil man. |

Fog had settled over the East End in a low, sour breath, the kind that slicked the cobbles and soaked the wool of the poor until it stank worse than the sheep it had been sheared and stolen from. She sat with her back to a brick wall, knees drawn up, fingers cramped into fists inside a man's cut-down gloves. A gift from a toff to a beggar, thinking he could buy sexual favours with his meagre offerings. She had run off clutching them. When was that? One night or twenty ago? She had no name to

put against the cold or the hunger. When she tried, it was as if she leaned over a well with no bottom and her voice fell, and never struck. Only sounds remained: a violin waltz, the hiss of gas, laughter in a room of mirrors; and worse - the quiet instruction of a man's voice close to her ear: drink.

Boots went past. A pair, then three. A shout further down, a scuffle. She tipped her head to keep watch from the corner of her eye. Men who looked too long at a woman who looked too poor. A cart wheel complained as it struck a rut. Somewhere a kettle lid clattered and a child cried and no one minded. She gathered herself smaller against the wall, a broken-winged bird trapped near the gutter in the rain.

"Miss?"

The voice came from the fog as if someone had opened a door onto a different room. Not the bark of a watchman, not the careless slur of a drunk; polite, precise, a tone that assumed an answer would be given because it always was.

She lifted her head. The man held a lantern low and turned the shield with thumb and forefinger so the light did not dash into her eyes. He wore a dark greatcoat, dry as if the fog respected its boundaries, and a hat with a narrow brim pressed into a firm line above his brow. Clean, that was the first certainty. The second was that he had a habit of looking without staring; his gaze touched and moved on like a physician's hand.

"Are you injured?" he asked.

She thought to say no. The word came as far as her teeth and broke. It was not pain so much as a general crack in her: raw, her shoulders aching from a coat too heavy and too stolen, her head full of a roar when she stood.

"I..." The sound rasped. To her surprise, her hands rose, the way a child's might when a parent returned from an ordinary day.

He set the lantern on the cobbles. "Forgive me," he said, "I am Dr Sebastian Veyl. May I take your pulse?"